Alzheimer’s Disease

Published Jan. 22, 2024

By Hopkins Medtech

Alzheimer’s Disease in the US

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) represents a mounting public health challenge. Most AD patients (>95%) are idiopathic and disease is characterized by late onset (80–90 years of age) with failure in the clearance of amyloid-b peptide (Ab) from the brain (Masters et al., 2015). The main symptoms of the disease are progressive memory deficits, cognitive impairment, and personality changes.

More than 6 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s. By 2050, this number is projected to rise to nearly 13 million.

As AD is difficult to diagnose clinically, biomarkers of underlying pathophysiology are playing an ever‐increasing role in research, clinical trials, and in the clinical work‐up of patients.

Though cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and positron emission tomography (PET)‐based measures are available, their use is not widespread due to limitations, including high costs and perceived invasiveness.

As a result of rapid advances in the development of ultra‐sensitive assays, the levels of pathological brain‐ and AD‐related proteins can now be measured in blood, with recent work showing promising results.

7 in 10 Americans would want to know early if they have Alzheimer’s disease if it could allow for earlier treatment.

Key Features of Alzheimer’s Disease

Neuronal Damage and Death: Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the abnormal accumulation of two types of protein in the brain: beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles. These proteins interfere with normal cellular function, leading to neuronal damage and death.

Progressive Cognitive Decline: The most prominent symptom is the gradual decline in cognitive abilities. Initially, this often involves short-term memory loss and difficulty in recalling recent events. As the disease progresses, it affects other cognitive functions such as language, reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms: Alzheimer’s patients may exhibit changes in behavior and mood. This can include agitation, anxiety, depression, irritability, and even aggression. Hallucinations and delusions may occur in the later stages.

Loss of Functional Independence: As the disease advances, individuals with Alzheimer’s lose the ability to perform daily tasks and self-care. This leads to increased dependency on caregivers for activities like eating, dressing, and bathing.

Impaired Spatial and Visual Abilities: Alzheimer’s can affect spatial perception and visual processing, leading to difficulties in judging distances, identifying objects, and recognizing faces.

Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

Early Stage (Mild): Mild memory loss, difficulty finding the right words, and challenges with daily tasks.

Middle Stage (Moderate): Increased memory loss, confusion, mood swings, and trouble recognizing family and friends.

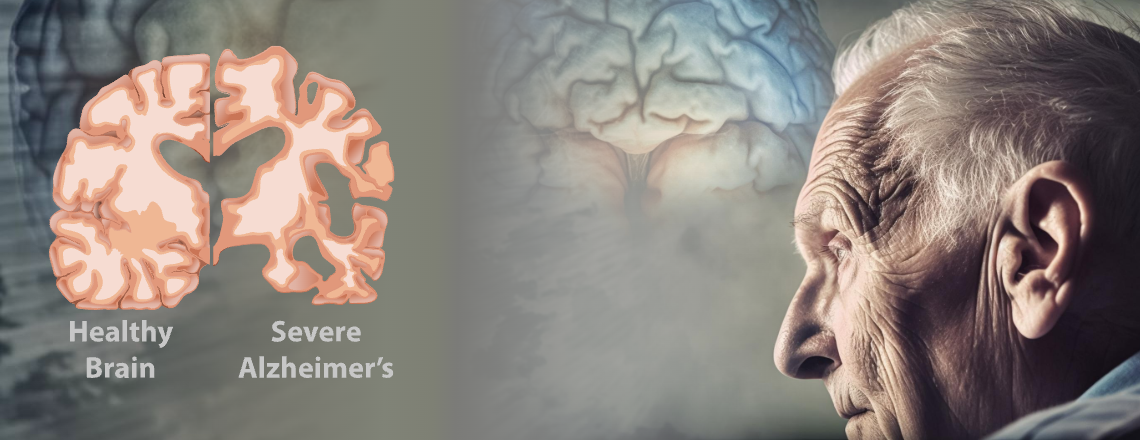

Late Stage (Severe): Severe cognitive decline, loss of communication abilities, complete dependence on others for care.

Promising biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AD): Amyloid Beta, pTau, and S-100

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a debilitating neurodegenerative disease characterized by the accumulation of two proteins in fibrillar form: amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau.

Amyloid-β40 and Amyloid-β42: Amyloid beta (Aβ) peptides are one of the most widely researched biomarkers for Alzheimer’s, MCI, dementia, and other cognitive disorders. In a diseased state, Aβ accumulates in the brain and forms extracellular plaques, which likely play a crucial role in the neurodegenerative processes.

Aβ deposition may begin two decades before clinically noticeable cognitive impairment (Selkoe et al., 2016), at which point Aβ levels in the surrounding fluid decline before eventually reaching a plateau.

Aβ40 is considered an initiating factor of AD plaques. In healthy and disease states, Aβ40 is the most abundant form of the amyloid peptides in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma, with an average concentration of 10–20X higher than Aβ42.

In addition to measuring Aβ40 and Aβ42 individually, researchers commonly look at the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio to distinguish AD from non-AD patients (Lehmann et al., 2018). Furthermore, the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio is uniquely useful as an ongoing measurement indicative of AD progression.

pTau Protein: Studies show that p-tau181 is increased 3.5-fold in AD patients and could distinguish AD from other neurodegenerative disorders almost as accurately as PET scans and CSF measurements (Thijssen, 2020).

Plasma P‐tau appears to be the best candidate marker during symptomatic AD (i.e., prodromal AD and AD dementia) and preclinical AD when combined with Aβ42/Aβ40.2 Additionally, higher p-tau181 is associated with a steeper cognitive decline and gray matter loss in temporal regions (Simrén et al., 2021).

S100 Protein: Evidence strongly suggests a role of S100 proteins as key players in several AD-linked physiopathological processes. S100 proteins are calcium-binding proteins that regulate several processes associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Due to neuroinflammation in AD patients, the levels of several S100 proteins are increased in the brain and some S100s play roles related to the processing of the amyloid precursor protein, regulation of amyloid beta peptide (Ab) levels, and Tau phosphorylation.