Many people, both adults and adolescents, are afraid of needles being inserted into the skin to draw blood. It makes them uncomfortable when medical personnel collect blood samples from their arms. Of course, there is an alternative method: pricking the fingertip or earlobe. However, for many laboratory tests, a drop of blood obtained from these locations is not enough. Most importantly, the tests conducted with them are often inaccurate: laboratory values fluctuate across different measurements.

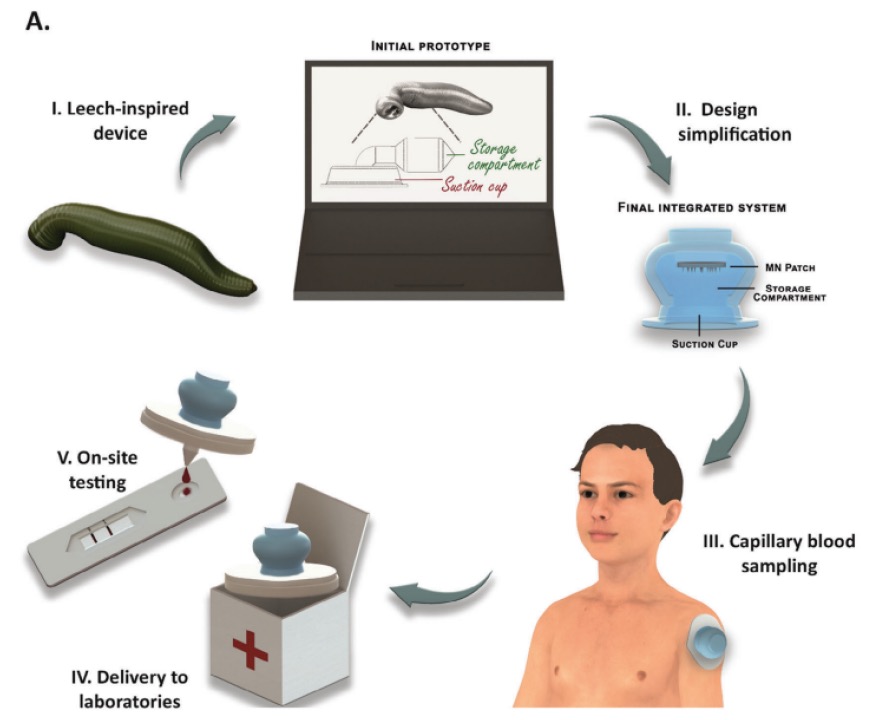

Researchers at ETH Zurich have developed a new device for collecting blood samples. It works on the principle of leeches and is less invasive than obtaining blood with a needle from the arm. It is also easy to operate and can be used by people without medical training. Although the new device collects less blood than a needle, it gathers much more blood than pricking a finger does. This makes diagnostic measurements more reliable.

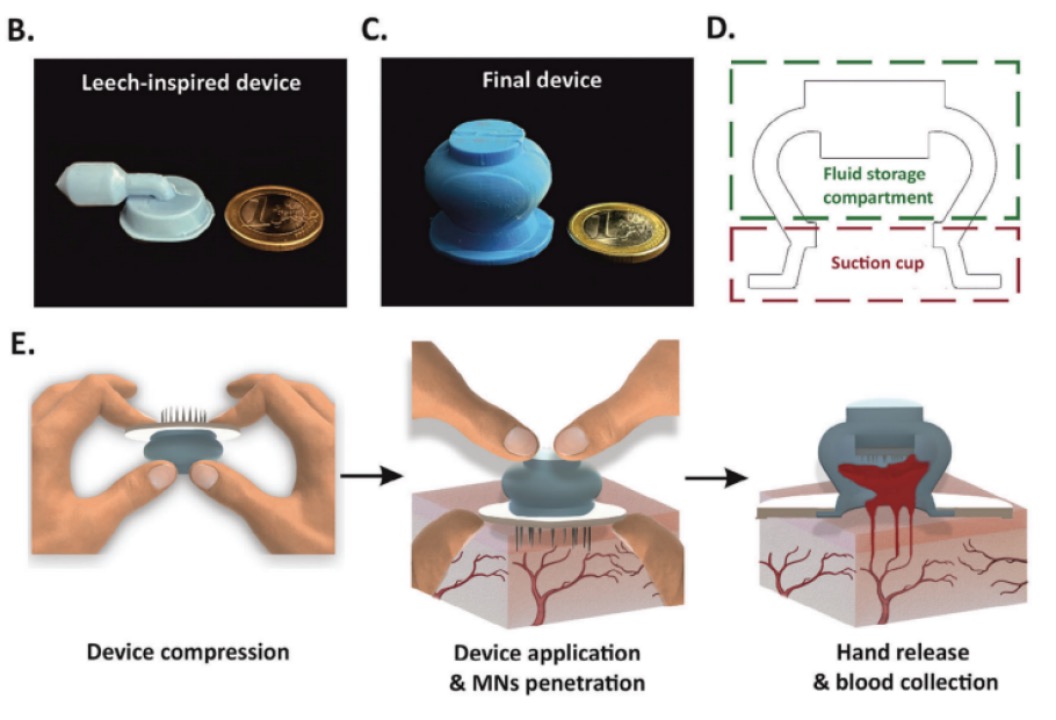

By studying leeches, it was discovered that they attach to their host with a suction cup. The researchers realized that a similar system could be developed to collect blood. After attaching, leeches pierce the host’s skin with their teeth. To draw blood from the wound, they generate a vacuum by sucking. The working principle of the new device is very similar: a suction cup about two and a half centimeters in diameter is fixed onto the patient’s upper arm or back. Inside the cup, there are twelve microneedles that pierce the skin when pressed onto it. Within a few minutes, the vacuum in the suction cup ensures sufficient blood is collected for diagnostic tests.

This new device will be utilized in low-income areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa in the future, playing a significant role in the fight against tropical diseases like malaria. Diagnosing malaria requires drawing blood from the patient. Another advantage of the new device is that the microneedles are located inside the suction cup. Compared with using traditional needles for blood collection, this can greatly reduce the risk of injury during use and handling. In the current version of the leech-like device, the suction cup is made of silicone, and the hidden microneedles are made of steel. However, researchers are developing a new version made entirely of biodegradable materials to create a sustainable product.

Before this device is widely used in humans (in malaria regions and elsewhere), its material components still need optimization. Most importantly, safe use must be tested by a small group of test subjects. Because such research is complex and expensive, the research team is still looking for partners to obtain further funding, such as from charitable foundations. They hope that their new leech device will soon play a role in the health of children and others who are afraid of needles.